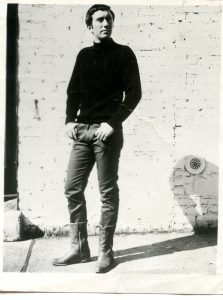

My older brother, Owen, was a poet, an actor, and playwright. And, he was gay.

It was especially not ok to be gay in our family while growing up in the 1950s in Pennsylvania. Maybe if there had been gay characters on family sitcoms and gay journalists on network television, as there are now, our parents would have been able to accept Owen and give him the love he deserved. But, they needed society’s approval to love their child and in the 1950s my parent’s didn’t have that approval.

Yet, what if they had loved Owen by courageously not caring what society thought about their own child?

When I was in my twenties I worked at a day care center. We had a little 3 year old boy there who was always the first to be picked up. His father would walk through the door whistling the Irving Berlin song, “Always.” Wherever the little boy was, he’d hear that song and knew it was meant only for him. He’d jump up, the castle of blocks he’d spent so much time building, knocked over and forgotten, as he ran into the man’s outstretched arms. The man would swing the boy up and hug him so tight, you just knew the boy would soar through life, like floating from a trapeze, because the man was his net.

The man would laugh. The boy would laugh. Their laughter sounded like home, or the way I imagined home could sound like. And I laughed too at their happiness and love.

One day the man said to me of the boy, “He’s very sensitive. I can tell he’s going to be an actor like me. Look at our hands. They’re so alike.” He held up his hand and put the little 3 year old boy’s hand next to his for me to examine. The man’s hands were small, the fingers tapered, the nails well cared for. Hands of a musician, I thought, before he told me he was an actor.

The little boy was small for his age, and frail like the man. The child was the man’s girlfriend’s son. None of his genes had been transferred to this boy he was so proud of, but it made no difference to him. The two sets of hands were nondescript. Nothing you’d remember, really. Except I have remembered. For over forty years I’ve remembered his hands and those of the little boy. Not because they were so similar, as the man wanted me to believe, but because I felt the profound love the man had for the boy, which made me love him. To me the man had hands that did no harm. To Owen and me our father’s hands were capable—not careful.

That is why the concept a man was capable of respecting a child was unknown to me. The profound respect and deep love of this man for this child was not what I experienced in our family growing up. It was foreign, like traveling to a distant country where Owen and I did not speak the language. Yet, through this man and this child I understood the possibilities of what could be.

I remember looking at the man and at the little boy. All I could think was, why hadn’t Owen been born into this family? To a father who would welcome him and appreciate him for his talents as a poet, a playwright, and actor. A father who would be proud to call him son? Not a father who beat and abused Owen when he was the same age as the little boy standing in front of me. And the beatings and abuse were for what? For not being like whom? For not being like him? For being too much like him?

Our father would have names for this man who was in touch with his feminine side and they wouldn’t have been artistic and talented. Panty waist and queer were the names Owen and I heard in our house.

“Stand up straight! Give me a firm handshake, not that limp noodle! Lower your voice!” Father demanded.

I think of my father’s hands that were so different from the hands of the kind man. My father’s hands were large and hard, rough, dry and red, with deep lines. They were the hands of a man who didn’t mind getting them dirty. No matter how much he scrubbed them there was always remnants of dirt under his nails. With his capable hands he could fix a leaking toilet, wire a chandelier, or mend a fence. And, Owen and I knew, when he hit you with one of those hands, you remembered it.

Despite Owen’s lifelong mantra, “To thine own self be true,” he was as much a stranger to himself as he was to everyone who knew him. Whenever you asked him how he was, he would always say, fine. I know that all of his adult life Owen suffered in silence, just as he’d suffered in silence as a child, every time our father took off his belt and beat him with it.

My brother committed suicide on March 26, 1999. He hanged himself with two belts in his fifth floor walk-up apartment, freeing himself at last from the guilt and shame that eventually destroyed him. He’d been taught to believe that something was wrong with him. He was taught that he was a disappointment. He was taught artistic and kind were not okay for “real” men.

The people who loved Owen, including his small band of friends, weren’t able to convince him he was worthy and that there was nothing wrong with his being gay. I was not able to convince my brother either. But, I am grateful all these years later that the culture is changing. Which gives me great hope for future generations.

I watch my two year old grandson running around the garden wearing fairy wings like his older sister. Maybe he wants to be his older sister. Maybe he just likes wearing fairy wings. I don’t know. What I do know is that in our family he is loved and accepted and will be supported for whoever he is. My family freely gives him the respect, acceptance, and deep love that I wanted so desperately for my dear brother. A love and acceptance each of us has the power to give one another, no matter how beautifully different we are.